Everyone’s had the blues, or forgotten things, or struggled in one way or another at some point. It’s part of being human. But. Pause. Big Breath. Even when it sounds like shared symptoms are in the mix, even when it sounds like we can or should relate, typical human struggles are not the same as neuro-spicy experience.

From the safety of Normal Harbor—where most human brains hang out—it can be hard to imagine or understand the distinct experiences of people living with mental illness and/or neurodivergence. It can be challenging to believe that they are fundamentally different from the hurricane-in-a-safe-harbor bad times, the supercalifragilistic good times, and the ho-hum humdrum everyday that most people know.

But for those of us sailing well off-shore in Divergent Waters, we know too well that some brains just plain work differently, that they are different, and when we head for the harbor, it can feel especially challenging to join the party. Even well meaning neurotypical people seem to misunderstand much of the time, leaving a lot of people feeling isolated and alone. Navigating the divide can perplex everyone.

All of which is to say, what a great gift Jennifer offers this week on FED to guide us toward a shared shore. She intimately invites us into her experience of mental illness and artmaking like few I’ve read. She simultaneously achieves this feat as art, document, and meta-analysis so that we, too, may be included, may see the world as she experiences it and creates art from it, with it, despite it, in the midst of it, and beyond. With her poetry, video-poem, and story, Jennifer transports us from the bland land of typical vs a- to the utterly rich embedded in the species in all its infinite variation and possibility.

She sets the compass so we may begin to chart a course to emotion as time, as space. With no judgment, she relieves us from the burden of normal and, by example and inspiration, invites us to revel in her strange, brilliant, unusual consciousness and process, no matter the challenge, no matter the joy. Here lies compassion—for self and other—that we can all work with.

Big love, Ashley

P.S. Poetry is put on the page intentionally, while devices tend to like doing things so you can fit it all in your pocket. FED has preserved Jennifer’s intended line breaks so you get the work the way she meant it. To fully appreciate it, please read it on the biggest screen you have, or at least, turn your phone sideways to maximize screen width because the shape of this work is not well suited to tiny screens with minds of their own. So, put it on the table, folks. Because who wants a delectable dish served in a pocket?!? Bon appétit!

The question “what is happiness” can either be a question with simple answers (family, friends, fulfilling work, balance) or one that is more complicated to answer when you have all these things and still cannot feel anything but dread. This is the case with mental illness, specifically depression, which is one of the illnesses I’m susceptible to as a person with bipolar disorder.

Mania is more easily managed—there are strong pills to calm you down and knock you back into reality. Psychosis is more difficult because it takes a long time to reenter the real world. But depression is the most difficult—medications have very little efficacy, and once your brain stops registering pleasure, it’s hard to “cheer up” no matter the circumstances.

The last depression I faced was a nearly catatonic one. It started on the day of a polar vortex here in Michigan where I live, and it lasted for over a year. Nothing was ostensibly “wrong.” My brain had just begun slowing down, shutting down, and on that day, with a cold front that ushered in temperatures of 40 below with wind chill, my brain froze. I could hardly speak. It was hard to understand what people were saying and difficult to retain information at all. The idea of food or eating made me nauseated. I couldn’t think clearly enough or at a speed that made it possible for me to do the work I do (which I love doing—I teach writing at an art school, which was always my dream job). I laid in bed for months after that, trying not to contemplate suicide and failing. I finally called my parents to come and watch over me.

But during that time I also continued trying to write. I didn’t know if it was good and didn’t care. My fingers just pressed words into the computer as a desperate way to do something I knew once made me feel good. I didn’t go back to look at this writing until long after I was well again (the solution was that ketamine became available and saved me just weeks before shock therapy was being ordered). But when I did return to some of the poetry of that time, I found they were my favorite poems I had ever written.

My poetry is almost always about dealing with mental illness, but my book had focused on the recovery from mania and psychosis (which is the other side of the illness). I had never thought anything would be retrievable from a depression because it was just too dark and shut the brain down. But I had thwarted that belief.

Because I had written with no expectation it would be comprehensible or good—it was an act of defiance against a brain I assumed could do nothing. The poems I discovered were strange and unfiltered and written in strange forms, using unexpected language, that captured a person trying to make sense of things and climb out of a dark place. And I was proud of myself for doing my best to try to process that difficult time in some way.

Here’s an excerpt from one of the poems, which I eventually came to call “Psalms of Lament for Divine Imperatives.”

I wake before dawn with murder on my mind.

The city doesn’t love me. Or I don’t love it.

The slope of the earth isn’t right.

I feel it in my teeth the grit of mulch and fern

as the instant replay button sticks and I miss

my last homicidal mission.

I need to prepare my lessons to be a better citizen.

But the hours slip their fingers into breakfast cereals.

Was I under the impression that the afterlife is better?

I sit alone at the table and gloom

is in the next room where I left my sneakers

because sleeping is easier than jogging. Because

there’s a jog in my breath. Because the trickster

and the backhoe. Because I have parents

and friends who would miss me. Because

simple elements combine to make complex ones

and eventually become medicine.

In the hospital a woman who had

post-partum depression was asked

what she was thinking. She said listlessly

“The baby needs to eat.”

Because babies need to eat. Because therapy

and monopolies. Because maybe God

will arrive one day and I’ll want to be here

to see if he can fix things.

Though I knew I had typed these words in desperation, when I read them later I could see a hope in them—the hope that expressing how I felt might help me at least remember who I was. There is such a void of self in the state of depression.

The poem that most echoed the way my mind was working at the time was called “When Asked What Is Happiness?” I had no memory of writing it. It begins like this:

Like a pill in punctuation form

only the other way around.

Typed letters look like felt in a certain light.

Trifles, not trivets, tricycles, not tickets.

A tree without a face.

A brick wall, glowing iron in the sulfur

of the setting sun. A man draws a gun,

so beautiful and desirous for the hand.

Everyone scatters. The story ends there.

In another story, Judith holds up Holofernes’ head.

She has a knife. There is very little blood.

When you rush into,

if you rush into, the way you

rush into, don’t rush.

In this poem, read from a distance as a more coherent self, I could see the paradox of depression as well as the mental imagery that haunted me involuntarily during that time. In the unfinished thoughts, the thoughts that cancelled themselves out, I could see my mind earnestly trying figure out what happiness could be from a place where it was impossible to even imagine it.

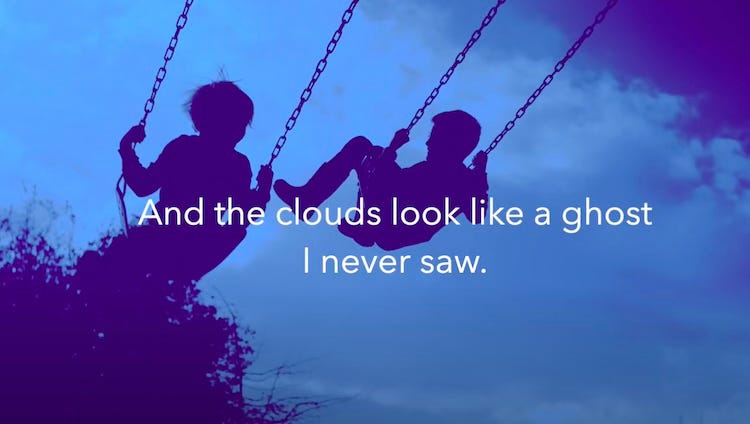

I ended up turning this poem into a video piece, collaborating with a friend who makes electronic music, Daniel Howard. I wanted to make a piece that had that feeling of the glitch of the brain at that time; so, I collaged together many open source videos of glitches and set glitch to music. The result is something a bit more playful than my depression felt, but still has that earnestness in seeking what happiness actually is.

The answer to this question remains unknown to me—I could certainly fall into this state again in my lifetime. But I think, if it happens again I will remember the meaningful aspect perseverance—even if happiness isn’t possible in that moment. The end of the poem expresses gratitude for words (I’d like to thank the alphabet for making all of this possible). Even then I must have know that words were somehow saving me, reminding me of who I am and letting me love my nearly erased self from a distance.

Here is the video:

FED is a participant-supported publication and community. Free subscriptions are a gift to all from other readers, contributors, and the editor. Paying subscribers both get a gift and give a gift by first, receiving their free subscription from the community and then, passing the gift on to others, via upgrade, in one great circle of giving and receiving.

All are welcome at the table, and together, we co-create and sustain community.

For more goodies…

Learn more about Jennifer and FED’s entire Summer 2024 global crew of musicians, artists, writers, growers, gleaners, cooks, and craftspeople, and be sure to check out all the tasty morsels we're serving up this season plus Jennifer’s Depression Green Smoothie recipe, which drops Thursday, 15 August.