Oh, the Mountains We Climb

Climber-photographer Peter Golcher serves up a mighty good Yosemite view

It’s been a long time since I was a multi-pitch climber, but metaphorically speaking, Saku and I have been scaling some pretty challenging rocks lately. Recently, the piton securing us pulled loose on an especially terrifying overhang, and we dangled precariously above the precipice, swinging like a pendulum, with more adrenaline than feels good coursing every which way.

Thanks to the careful scaffolding placed along the route below this failed piton—good friends, tested skills, and no small measure of luck—we are now back on the rock face. Although I am too battered and bruised for comfort, I’m once again climbing toward a safe finish for one hell of a gnarly route, one I hope never again to traverse.

Nothing from my actual climbing days came close to approximating this recent metaphorical fall and the fear it instilled, but I’ve lost friends to the rocks, heard countless stories of crippling breaks—backs, legs, arms, heads—and never once did I climb without first getting physically sick.

Heights scare me because the risks are existential. Even remembering these climbing days in order to write this for you, makes me sweat. I can feel myself looking up the rock, my guts screaming “no,” climbing into my harness anyway, clipping in, and putting that first hand on granite, that first toe on a little nubbin, then calling “climbing,” to my partner. “Climb on,” he replies, and against gravity and gut-sense, I pull myself toward the sky.

Not long after Peter and I met, he took a hair-raising fall from a rock face in California’s High Sierra. While leading a multi-pitch climb, he slipped, as we all do sometimes, protection failed, as we all hope it never will, and he bounced and swung his way down a lot more rock than I want to imagine before landing with substantial but miraculously, not overly or ultimately damaging injuries.

Despite the fall, he keeps climbing. In fact, he climbs regularly and with relish and gusto. Just about every climber I know finds their way back to rocks, one way or another, over and over again, no matter the risks.

Literal and metaphorical tumbles, which is to say the risks, make me wonder why we climb. I don’t have a great answer to this question because for me, and unlike the guys I climbed with, adrenaline is a turn-off rather than a pull. I hate the rush. The pull is deeper and beyond any rush. Even while I know the risks, instinctively and from experience, I also know that great risk ultimately yields the most spectacular vistas.

So, maybe the risk is worth it because the climb itself, and the view from the top, offer fundamental living, are living. In short, maybe we climb, I climb (now, only metaphorically, but with apparently unrelenting gusto), because living large—authentically, audaciously, and passionately—is worth it. Fear and falls be damned.

So, sweaty and bruised and clinging to a gnarly rock, not yet at the summit and full of far too much adrenaline, I say, “here’s to the climb; here’s to the view!” And, what a mighty view, Peter offers us this week from his climbs in Yosemite.

Tourists visiting Yosemite National Park are treated to spectacular views from roadside turnouts and accessible paths. They’ve been memorialized on postcards, placemats, and t-shirts found round the world. These aren’t the only views, however, and Peter takes us to the backcountry and to the rocks themselves to bring us six unique glimpses of these sites and sights. He offers us a remarkable shift in perspective as he takes us on a journey through memory.

Big love, Ashley

In Yosemite, Some Mighty Good Views

My long-suffering climbing partner is a guy named Ron. This series grew out of a conversation we had as we drove out to Yosemite to climb Royal Arches this summer. We've talked about odd things during our travels over the years … why are clouds the height they are; whiskey or whisky (+ how unhealthy?); how to resolve the geopolitical crisis of the day; wheat in beer, good or bad; other things. Geezer philosophers to the core.

This time, our talk turned to memories: how many memories do we have; how many experiences do we manage to preserve within our mind's eye and keep available for immediate recall; more. From our earliest moment, how many memories can we relive? I can clearly recall the 1969 moon landing and punching another four year-old, who badmouthed my two year-old sister. A distinct memory of being with my Grandfather when I was two or three (& my Grandmother getting really upset at his bad behavior… I can still clearly remember his laugh that day).

The following photographs capture memories. Either deliberately or passively, I look to preserve the wild beauty of the natural world with photography, and also—perhaps more importantly—the experience so that I may bring back the emotional connection of the moment.—Peter Golcher

Sunrise over Half Dome

4am. Coming downhill and around the corner of highway 41, knowing the first view of "The Valley" was immediately ahead. Before dawn, but close enough so that the dawn equivalent of twilight was warming the sky. While time was precious—we needed to be first on the route to finish our climb and be down before dark—and while I have driven this road often, the view was too special to let pass.

This time, a striking, if not breathtaking, silhouette with the skyline defined by Half Dome. Sun starting to appear, giving a wash to the clear sky. It’s one of my favorite recent memories of Half Dome because, for me, the photo captures and preserves my anticipation of the coming climbing adventures. A photograph that preserves my emotional connection to the moment, if you will.

The Stagecoach Road

I had known of the old road and had picked its path from Discovery View1 many times as well as traced it out on historical maps. I like to refer to it by its less formal name, The Stagecoach Road. When visitors look down to the left from the Discovery View turnout, they see the highway they drove into the valley, but very few notice the old road, a mere scar across the hillside, barely discernible.

So, with a day to spare, and almost on a whim, I decided to take a closer look. I hunted for the remnants of where I knew the old road connected with Northside Drive in the valley, and off, on another adventure I went.

The view from The Stagecoach Road was the first pioneers saw of Yosemite Valley as they came in past the now-historic Rainbow View. But today, The Stagecoach Road view is essentially unknown. “Discovery” of Yosemite's now-famed grandeur followed the arrival of the first pioneers almost immediately, and Discovery View became the famous perspective we all know, but the view from The Stagecoach Road is one of the most impressive valley views, which I confirmed for myself while standing on the wrecked old road bed, high on the mountainside, admiring.

Looking toward the east end of the valley from fairly high above the valley floor, El Capitan is truly massive, perhaps more so here than from any other view. Across, to the right and level with the rim is Bridalveil Fall. Muir and Whitney stood on opposite sides of the geology debate, but looking at these features today from this view makes it hard to understand how a Harvard geology professor got it wrong. Glaciated nature clearly carved these features.

These views are, for me, some of the most special. I tried (completely unsuccessfully) to set my photographs from that day to Robert Frost, but despite my best efforts, I could not dovetail New England poetry with a Yosemite scramble in any meaningful way. That fruitless exercise (!) eventually became part of the broader "experience."

Bridalveil Fall Rainbow, from Discovery View

Late afternoon found us at Discovery View Center. Left is El Capitan, in the distance is Half Dome, and center-right is Bridalveil Fall.

I usually scan the valley seeking out familiar landmarks, seeking out differences from the last time I saw them. In spring, I was interested in snow on Half Dome; curious about cloud cover on Clouds Rest, whether smoke in the valley from the controlled burns was clearing, and so on.

This time, none of that. Instead, I was captivated by the Bridalveil rainbow. The lowering sun combined with the heavy spray from the rushing waterfall to create a unique rainbow. Many things had to come together in that instant: the angle and brilliance of the light had to be just right; the flow of Bridalveil Creek had to have sufficient volume over the fall and a solid breeze had to create volume for the spray.

I could almost feel a tightness in my chest from the sense of experiencing something really quite special.

The sharp-eyed may make special note that the rainbow experience from Discovery View is probably similar to the experience from the pioneers’ Rainbow View, but separated by over a hundred years.

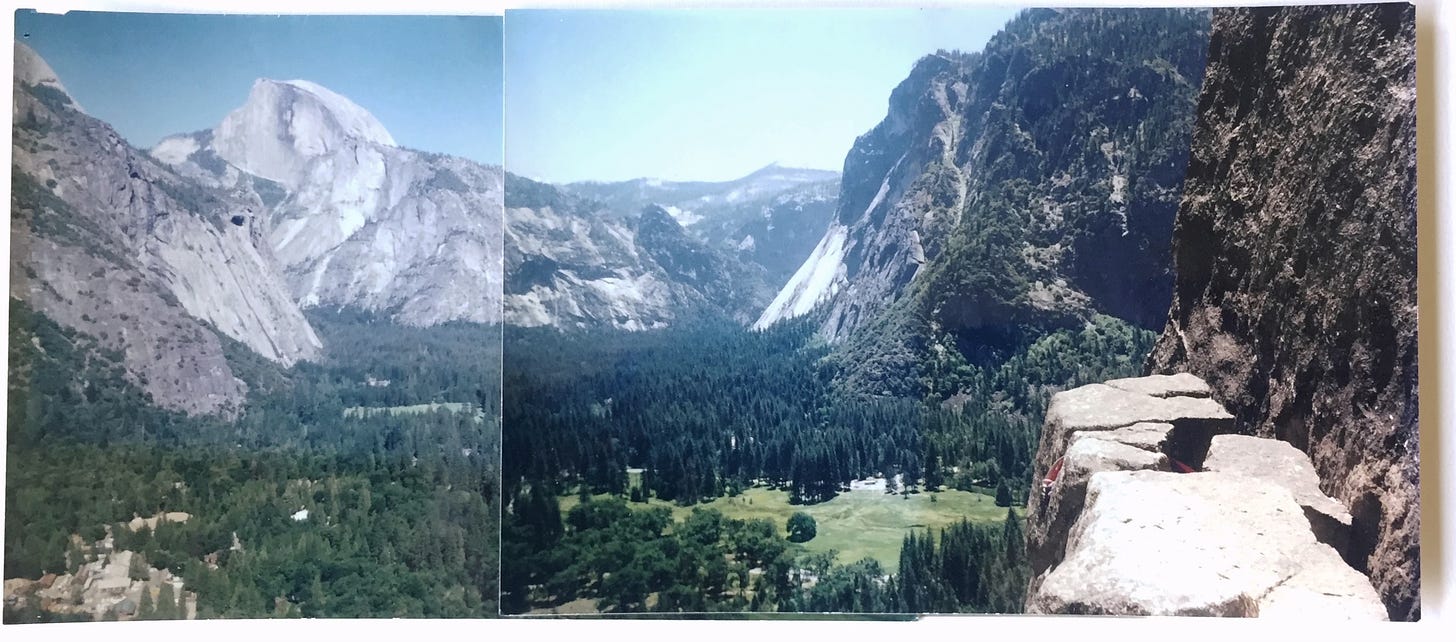

Yosemite Old School Panorama

My first Yosemite climb lives on through a silly pair of photographs collected quickly while sitting on a ledge a few hundred feet off the ground and coupled together with adhesive tape to create a 1990’s era panorama.

Unremarkable photo of a ledge on an unremarkable climb, some distance above the ground from a year I only vaguely remember.

All of which is completely untrue.

They say climbers have some of the best views in Yosemite since we are generally above the tree line and can fully experience the environment. I wouldn’t disagree.

This photo was taken on my first climb in Yosemite Valley. As a group of four, we climbed Munginella and Selaginella. Two classic Yosemite climbs in the area known as Five Open Books, close to Yosemite Falls. Starting at dawn, I reached these distinctive ledges early and somehow wanted to capture the sights and sounds with a panorama.

We took our pictures and climbed on. From the top of Munginella we scrambled over to the start of Selaginella, then climbed to the top, arriving at dusk, followed by a long hike back to the car.

The following journal entry hints at just how remarkable that climb and view actually were:

Climbing in Yosemite, such a marvelous experience. The sheer size of the walls is often imposing and can make long climbs evolve into unexpected overnight adventures. I clearly remember being poised on the ledge, taking these photos with a little point and shoot Olympus film camera that I had picked up years before in Naples at the store on the NATO base. This was going to be a long day, and we had no idea what we were in for. A day that would touch every single one of our senses and emotions.

At the time, the only way I knew how to create a panorama was to take a sequential set of photos and later - if the resulting pictures lined up with any degree of precision - create the picture. With this pair of photos, I was lucky. I hope you agree!

The primitive nature of this panorama—once loosely pinned to my office wall—still holds my attention. It is missing the absolute precision of accurate photographic fixturing, or modern AI tools, but for every aspect it lacks, it gains more.

Sunset on El Capitan, from Southside Drive

It is amazing how within a photo all of the surrounding details come to life. What I mean is that this picture launches me into an experience far broader and much deeper than the image itself.

We had just finished a climb in the valley and were heading back to the cabin, grateful to be off the wall before dark and looking forward to an evening with friends. We circled around from Northside Drive and across the Pohono Bridge, onto Southside. Past a marker on the right commemorating President Taft.

I have no idea why those details are important to this story, but they are indeed part of the tale! Immediately in front of us was El Capitan, but El Cap like I had never seen before, almost glowing orange in the last ephemeral light of the day: alpenglow. Heart Ledge lit up with brilliance.

In my journal, I wrote:

I don't know how to describe the senses that I still hold from that moment; all I can call it is the "character of light," but does that make any sense?

People wait for an hour or more at special spots in the valley, searching and waiting with long lenses on exquisite cameras for that special moment, the goal being to capture perfect alpenglow on the mountains. I'd almost cheated "the process." I came around a curve in the road, naïve and unknowing, and found something so spectacular that I immediately stopped and jumped out with whatever camera I had at hand.

Less than 90 seconds later, the light was gone.

Rappel from Royal Arches

We completed the climb we started at 4am, at a nice pace and in good time leaving us 1500 feet above the valley floor, trees far below. We had two hours of hard rope work before our feet would be back on the ground.

From my journal:

Standing on this face for the first time was striking—looking down, with the ground far below, senses gobsmacked by the seriousness of the accomplishment.

I grabbed a camera so I could capture the (raw) feelings that sometimes come with these accomplishments.

Looking down, I saw our rappel ropes trailing below, flat across the blank wall. The emotion of finishing a great and famous climb. Knowing and sensing - understanding, even - the work to come.

The end of a climb is not the end of the adventure; on occasion, it can be merely a pause between what has been accomplished and what is to come.

For us, the end was hours away.

Perhaps the most popular view of Yosemite Valley, “Discovery View,” is from the east end of Wawona Tunnel. From the comfort of the large parking lot, guests enjoy an overview of the valley, which spreads out in front, with the sheer face of El Capitan slightly to the left, Half Dome at the far end, and Bridaveil Fall to the right.

FED is a participant-supported publication and community. Free subscriptions are a gift to all from other readers, contributors, and the editor. Paying subscribers both get a gift and give a gift by first, receiving their free subscription from the community and then, passing the gift on to others, via upgrade, in one great circle of giving and receiving.

All are welcome at the table, and together, we co-create and sustain community.

For more goodies…

Learn more about Peter and FED’s entire Summer 2024 global crew of musicians, artists, writers, growers, gleaners, cooks, and craftspeople, and be sure to check out all the tasty morsels we're serving up this season including Peter’s Black Eyed Pea Vegetable Jambalaya, which drops next week.